Can a People-Centered New Urbanization Strategy Alleviate Household Energy Poverty

-

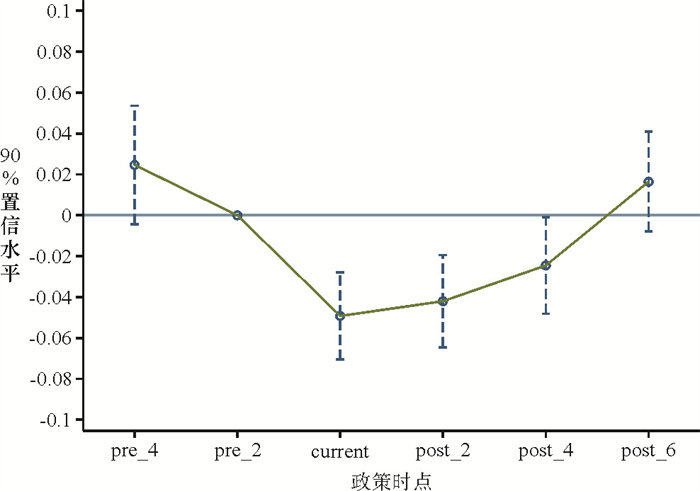

摘要: 以新型城镇化综合试点政策作为准自然实验,运用多期双重差分法研究新型城镇化对家庭能源贫困的影响效应和内在机理。结果表明:实施以人为本的新型城镇化战略有助于显著缓解家庭能源贫困,这一结论经过一系列检验后仍成立;增加居民收入、提高能源效率、增加社会资本是新型城镇化减轻能源贫困的重要渠道;新型城镇化对农村家庭、受教育程度较低、处于衰退期、地区资源依赖较低和能源需求较高家庭的能源贫困抑制效应更加明显;拓展性分析从非正式制度的视角探讨了家庭中女性相对地位对能源购买和使用决策的影响,指出新型城镇化对受儒家文化影响更深的农村家庭的能源贫困缓解效应更强。本研究对于新时代背景下我国相对贫困的治理和共同富裕的实现具有一定的参考价值。Abstract: Using the comprehensive pilot policy for new urbanization as a quasi-natural experiment, this study employs a multi-period difference-in-differences approach to examine the impact of new urbanization on household energy poverty and its underlying mechanisms. The findings are as follows: implementing a people-centered new urbanization strategy significantly alleviates household energy poverty, and this conclusion remains robust across a series of tests; increasing resident income, improving energy efficiency, and enhancing social capital are the critical channels through which new urbanization mitigates energy poverty; the suppressive effect of new urbanization on household energy poverty is more pronounced for rural households, those with lower education, households in declining periods, those with lower regional resource dependence and higher energy demands. Extended analysis explores the impact of women's relative status in households on energy purchasing and usage decisions from the perspective of informal institutions. The results reveal that the impact of new urbanization on household energy poverty is more significant in rural households, which are more deeply influenced by Confucian culture. This study provides valuable insights for further promoting relative poverty governance and common prosperity in the context of China's new era.

-

Key words:

- new urbanization /

- household energy poverty /

- resident income /

- energy efficiency /

- social capital

-

表 1 基准回归结果

变量 (1) (2) (3) Newcity -0.045*** -0.034*** -0.036*** (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) age 0.006*** 0.005*** (0.000) (0.000) gender 0.035*** 0.027*** (0.005) (0.006) hukou 0.263*** 0.272*** (0.008) (0.008) marriage -0.085*** -0.065*** (0.008) (0.008) edu -0.016*** -0.016*** (0.001) (0.001) health 0.021*** 0.021*** (0.002) (0.002) familysize -0.022*** (0.002) child 0.030*** (0.004) old 0.045*** (0.004) 常数项 1.497*** 1.123*** 1.186*** (0.004) (0.019) (0.021) 地区固定效应 是 是 是 时间固定效应 是 是 是 样本量 57 973 56 124 56 124 adj.R2 0.230 0.305 0.311 注:括号内为聚类稳健标准误;*、* *、* * *分别表示在10%、5%和1%的水平上显著;下表同。 表 2 稳健性检验:改变变量衡量、模型与样本

变量 (1)

EP_10%(2)

EP_20%(3)

EP_占比(4)

多维能源贫困(5)

EP(6)

EP(7)

EP替换被解释变量 改变模型 改变样本 Newcity -0.051*** -0.025*** -0.018*** -0.018*** -0.068*** -0.808*** -0.049*** (0.008) (0.006) (0.003) (0.005) (0.023) (0.026) (0.011) 常数项 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 控制变量 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 地区固定效应 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 时间固定效应 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 样本量 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 123 56 124 41 828 adj.R2 0.086 0.054 0.079 0.311 0.323 - 0.309 表 3 稳健性检验:排除干扰性政策

变量 (1)

电力市场改革试点(2)

碳排放权交易试点(3)

光电扶贫政策(4)

新能源示范城市试点(5)

低碳城市试点(6)

节能减排示范城市试点(7)

宽带中国试点(8)

智慧城市试点(9)

高速铁路开通(10)

国家公共文化服务示范区试点Newcity -0.031*** -0.034*** -0.035*** -0.036*** -0.032*** -0.037*** -0.034*** -0.029*** -0.039*** -0.038*** (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) (0.011) 常数项 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 控制变量 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 地区固定效应 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 时间固定效应 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 样本量 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 adj.R2 0.311 0.311 0.311 0.311 0.311 0.311 0.311 0.311 0.311 0.311 表 4 稳健性检验:异质性稳健估计量和合成双重差分

方法 Bacon分解 CSDID SDID (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) ATT -0.044 -0.044 -0.046 -0.044 -0.028** -0.026** -0.036* [0.018] [0.056] [0.926] (0.013) (0.0138) (0.021) 注:小括号内为标准误,中括号内为权重。 表 5 稳健性检验:双重机器学习和工具变量

变量 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) 1∶3分割 1∶5分割 IV估计 Randomforest Lassocv Gradboost Randomforest Lassocv Gradboost Newcity -0.115*** -0.073*** -0.069*** -0.117*** -0.067*** -0.072*** -0.245** (0.018) (0.018) (0.018) (0.019) (0.018) (0.018) (0.108) 常数项 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 控制变量 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 地区固定效应 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 时间固定效应 是 是 是 是 是 是 是 样本量 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 44 421 表 6 机制检验:居民收入

变量 (1)

家庭收入(2)

工资性收入(3)

经营性收入(4)

财产性收入(5)

转移性收入Newcity 0.401*** 0.206*** 0.013 0.020*** 0.059*** (0.055) (0.031) (0.014) (0.005) (0.019) 常数项 是 是 是 是 是 控制变量 是 是 是 是 是 地区固定效应 是 是 是 是 是 时间固定效应 是 是 是 是 是 样本量 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 56 124 adj.R2 0.245 0.287 0.037 0.092 0.241 表 7 机制检验:能源效率

变量 (1)

能源效率(2)

能源费(3)

燃料占比(4)

电能占比(5)

取暖占比(6)

家庭用能服务Newcity 0.006** -0.227*** -0.024*** 0.062*** -0.042*** 0.015** (0.003) (0.016) (0.005) (0.006) (0.003) (0.006) 常数项 是 是 是 是 是 是 控制变量 是 是 是 是 是 是 地区固定效应 是 是 是 是 是 是 时间固定效应 是 是 是 是 是 是 样本量 28 973 55 635 55 635 55 635 55 635 56 124 adj.R2 0.752 0.298 0.106 0.220 0.269 0.379 表 8 机制检验:社会资本

变量 (1)

认知性社会资本(2)

拥有结构性社会资本(3)

没有结构性社会资本Newcity 0.007** -0.039 -0.035*** (0.003) (0.033) (0.011) 常数项 是 是 是 控制变量 是 是 是 地区固定效应 是 是 是 时间固定效应 是 是 是 样本量 45 306 5 799 50 324 adj.R2 0.112 0.354 0.306 表 9 异质性分析

变量 (1) (2) (3) (4) 城乡 受教育程度 农村 城市 受教育程度低 受教育程度高 Newcity -0.053*** -0.010 -0.073*** 0.018 (0.014) (0.015) (0.016) (0.018) 样本量 39 367 16 755 28 479 27 645 adj.R2 0.273 0.190 0.268 0.275 变量 (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) 家庭生命周期 户主年龄 起步构建期 稳定成长期 衰退期 中青年 老年 Newcity -0.031* -0.008 -0.110*** -0.014 -0.094*** (0.017) (0.021) (0.028) (0.013) (0.022) 样本量 22 727 15 250 11 446 40 440 15 684 adj.R2 0.308 0.301 0.355 0.296 0.344 变量 (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) 地区资源依赖度 地区能源需求结构 资源型城市 非资源型城市 东部地区 中部地区 西部地区 Newcity -0.018 -0.035*** -0.020 -0.114*** -0.114*** (0.021) (0.013) (0.014) (0.023) (0.039) 样本量 21 110 35 014 26 186 13 926 12 318 adj.R2 0.288 0.299 0.303 0.286 0.274 注:回归中均加入了控制变量、地区固定效应和时间固定效应。 表 10 拓展性分析

变量 (1) (2) (3) (4) 受儒家文化影响较大 受儒家文化影响较小 全样本 农村 城市 全样本 Newcity -0.055*** -0.065*** -0.039** 0.007 (0.013) (0.016) (0.018) (0.020) 常数项 是 是 是 是 控制变量 是 是 是 是 地区固定效应 是 是 是 是 时间固定效应 是 是 是 是 样本量 32 809 24 035 8 772 23 315 adj.R2 0.319 0.275 0.206 0.300 -

[1] 刘华军, 石印, 郭立祥, 等. 新时代的中国能源革命: 历程、成就与展望[J]. 管理世界, 2022(7): 6-24. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-5502.2022.07.002 [2] DOGAN E, MADALENO M, INGLESI-LOTZ R, et al. Race and energy poverty: evidence from African-American households[J]. Energy Economics, 2022, 108: 105908. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2022.105908 [3] 何可, 朱信凯, 李凡略. 聚"碳"成"能": 碳交易政策如何缓解农村能源贫困?[J]. 管理世界, 2023(12): 122-144. [4] CHARLIER D, LEGENDRE B, RISCH A. Fuel poverty in residential housing: providing financial support versus combatting substandard housing[J]. Applied Economics, 2019, 51(49): 5369-5387. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2019.1613501 [5] 畅华仪, 何可, 张俊飚. 挣扎与妥协: 农村家庭缘何陷入能源贫困"陷阱"[J]. 中国人口·资源与环境, 2020(2): 11-20. [6] 杨丹, 邓明艳, 刘自敏. 提高能源效率可以降低相对贫困吗?——以能源贫困为例[J]. 财经研究, 2022(4): 4-18. [7] ACKERMANN K, CHURCHILL S A, SMYTH R. High-speed internet access and energy poverty[J]. Energy economics, 2023, 127: 107111. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2023.107111 [8] ZHANG D, LI J, HAN P. A multidimensional measure of energy poverty in China and its impacts on health: an empirical study based on the China family panel studies[J]. Energy Policy, 2019, 131: 72-81. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2019.04.037 [9] ZHANG Q, APPAU S, KODOM P L. Energy poverty, children's wellbeing and the mediating role of academic performance: evidence from China[J]. Energy Economics, 2021, 97: 105206. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105206 [10] ACHARYA R H, SADATH A C. Energy poverty and economic development: household-level evidence from India[J]. Energy and Buildings, 2019, 183: 785-791. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.11.047 [11] APERGIS N, POLEMIS M, SOURSOU S E. Energy poverty and education: fresh evidence from a panel of Developing countries[J]. Energy Economics, 2022, 106: 105430. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105430 [12] ABBAS K, LI S, XU D, et al. Do socioeconomic factors determine household multidimensional energy poverty? empirical evidence from South Asia[J]. Energy Policy, 2020, 146: 111754. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111754 [13] LIN B, WANG Y. Does energy poverty really exist in China? from the perspective of residential electricity consumption[J]. Energy Policy, 2020, 143: 111557. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111557 [14] 李兰冰, 高雪莲, 黄玖立. "十四五"时期中国新型城镇化发展重大问题展望[J]. 管理世界, 2020(11): 7-22. [15] LIN B, ZHAO H. Does off-farm work reduce energy poverty? evidence from rural China[J]. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 2021, 27: 1822-1829. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2021.04.023 [16] MA R, DENG L, JI Q, et al. Environmental regulations, clean energy access, and household energy poverty: evidence from China[J]. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 2022, 182: 121862. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121862 [17] CHANTARAT S, BARRETT C B. Social network capital, economic mobility and poverty traps[J]. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 2012, 10: 299-342. doi: 10.1007/s10888-011-9164-5 [18] LI H, LENG X, HU J, et al. When cooking meets confucianism: exploring the role of traditional culture in cooking energy poverty[J]. Energy Research & Social Science, 2023, 97: 102956. [19] AMPOFO A, MABEFAM M G. Religiosity and energy poverty: empirical evidence across countries[J]. Energy economics, 2021, 102: 105463. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105463 [20] CASALÓ LV, ESCARIO J J. Heterogeneity in the association between environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behavior: a multilevel regression approach[J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2018, 175: 155-163. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.237 [21] CRENTSIL A O, ASUMAN, D, FENNY A P. Assessing the determinants and drivers of multidimensional energy poverty in Ghana[J]. Energy Policy, 2019, 133: 110884. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2019.110884 [22] DU J, SONG M, XIE B. Eliminating energy poverty in Chinese households: a cognitive capability framework[J]. Renewable Energy, 2022, 192: 373-384. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2022.04.106 [23] 熊湘辉, 徐璋勇. 中国新型城镇化水平及动力因素测度研究[J]. 数量经济技术经济研究, 2018(2): 44-63. [24] 孙学涛, 于婷, 于法稳. 新型城镇化对共同富裕的影响及其作用机制——基于中国281个城市的分析[J]. 广东财经大学学报, 2022(2): 71-87. [25] 马彦瑞, 刘强. 新型城镇化建设的减污降碳效应[J]. 中国人口·资源与环境, 2024(1): 33-45. [26] 周闯, 郑旭刚, 许文立. 县域新型城镇化建设与农业转移人口就业质量[J]. 世界经济, 2024(4): 212-240. [27] 尤济红, 梁浚强. 新型城镇化、城市规模与流动人口收入提升[J]. 南开经济研究, 2023(9): 179-198. [28] 李军, 李敬. 新型城镇化能改善代际流动性吗?[J]. 劳动经济研究, 2020(1): 44-71. [29] 李子联. 新型城镇化与农民增收: 一个制度分析的视角[J]. 经济评论, 2014(3): 16-25. [30] ZHAO D, MCCOY A, DU J. An empirical study on the energy consumption in residential buildings after adopting green building standards[J]. Procedia Engineering, 2016, 145: 766-773. [31] LI J, ZUO X, SUN C. The effect of urban renewal on residential energy consumption expenditure—the example of shantytown renovation[J]. Energy Policy, 2023, 183: 113805. [32] BIENVENIDO-HUERTAS D, SÁNCHEZ-GARCÍA D, RUBIO-BELLIDO C, et al. Holistic analysis to reduce energy poverty in social dwellings in southern Spain considering envelope, systems, operational pattern, and income levels[J]. Energy, 2024, 288: 129796. [33] KRAUT R, PATTERSON M, LUNDMARK V, et al. Internet paradox: a social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being?[J]. American psychologist, 1998, 53(9): 1017. [34] 周晔馨. 社会资本是穷人的资本吗?——基于中国农户收入的经验证据[J]. 管理世界, 2012(7): 83-95. [35] NGUYEN C P, SU T D. The influences of government spending on energy poverty: evidence from Developing countries[J]. Energy, 2022, 238: 121785. [36] 张柯, 方时姣, 张振华. 心理账户视角下家庭收入对家庭能源消费与能源贫困的影响[J]. 资源科学, 2024(5): 895-909. [37] 吴施美, 郑新业. 收入增长与家庭能源消费阶梯——基于中国农村家庭能源消费调查数据的再检验[J]. 经济学(季刊), 2022(1): 45-66. [38] 朱鹏华, 刘学侠. 以人为核心的新型城镇化: 2035年发展目标与实践方略[J]. 改革, 2023(2): 47-61. [39] ALBERINI A, FILIPPINI M. Transient and persistent energy efficiency in the US residential sector: evidence from household-level data[J]. Energy Efficiency, 2018, 11: 589-601. [40] CIDADE E C, MOURA JR J F, NEPOMUCENO B B, et al. Poverty and fatalism: impacts on the community dynamics and on hope in Brazilian residents[J]. Journal of prevention & intervention in the community, 2016, 44(1): 51-62. [41] LUAN B, ZOU H, HUANG J. Digital divide and household energy poverty in China[J]. Energy Economics, 2023, 119: 106543. [42] 蔡宏波, 刘琳. 城市数字化转型与居民主观幸福感[J]. 经济理论与经济管理, 2023(12): 107-120. [43] GOODMAN-BACON A. Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing[J]. Journal of Econometrics, 2021, 225(2): 254-277. [44] CALLAWAY B, SANT'ANNA P H. Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods[J]. Journal of Econometrics, 2021, 225(2): 200-230. [45] ARKHANGELSKY D, ATHEY S, HIRSHBERG D A, et al. Synthetic difference-in-differences[J]. American Economic Review, 2021, 111(12): 4088-4118. [46] 张涛, 李均超. 网络基础设施、包容性绿色增长与地区差距——基于双重机器学习的因果推断[J]. 数量经济技术经济研究, 2023(4): 113-135. [47] 史丹, 李少林. 排污权交易制度与能源利用效率——对地级及以上城市的测度与实证[J]. 中国工业经济, 2020(9): 5-23. [48] 周广肃, 樊纲, 申广军. 收入差距、社会资本与健康水平——基于中国家庭追踪调查(CFPS)的实证分析[J]. 管理世界, 2014(7): 12-21. [49] DELLER D, TURNER G, PRICE C W. Energy poverty indicators: inconsistencies, implications and where next?[J]. Energy Economics, 2021, 103: 105551. [50] 刘爱玉, 佟新. 性别观念现状及其影响因素——基于第三期全国妇女地位调查[J]. 中国社会科学, 2014(2): 116-129. [51] 薛琪薪, 章志敏. 城乡人口流动与家庭性别意识的现代化与平权化——基于对上海、浙江和福建农村家庭的调查数据[J]. 南方人口, 2019(4): 1-14. [52] 田艳平, 李佳锶. 性别观念与家庭能源堆叠消费——基于微观调查数据的经验证据[J]. 山西财经大学学报, 2023(9): 35-48. [53] 孙超, 刘爱玉. 城镇化境遇及其对两性性别观念的型塑[J]. 人口与发展, 2020(5): 112-121. [54] JACOBS L, GUOPEI, G, HERBIG P. Confucian roots in China: a force for today's business[J]. Management Decision, 2012, 33(10): 29-34. [55] 徐细雄, 李万利, 陈西婵. 儒家文化与股价崩盘风险[J]. 会计研究, 2020(4): 143-150. -

下载:

下载: